Setting the Scene

Whilst South Indian traders have been known to trade in the region for 1500 years prior to European colonisation (Arasaratnam, 1970) and different European and Japanese colonial governments have occupied the land and ruled its people in the last 400 years, British colonial administrators led the migration of poor labourers from various South Indian states to what was known as Malaya from 1842 till 1917. The project explores empirically how different generations of urban poor Malaysian Indian women experience how coloniality manifests today.

Post-independence Malaysian society saw the exacerbation of conditions for Malaysian Indians as focus was placed on developing the Bumiputera population (Reddy & Selvanathan, 2019). As reported by Yayasan Pemulihan Social (YPS), the social welfare arm of the Malaysian Indian Congress, a sizeable 40% of the 2.6 million Indians living in the nation are reportedly stuck at the very bottom of the income distribution (Malay Mail, 2015).

Background Photo by Mogan Selvakannu

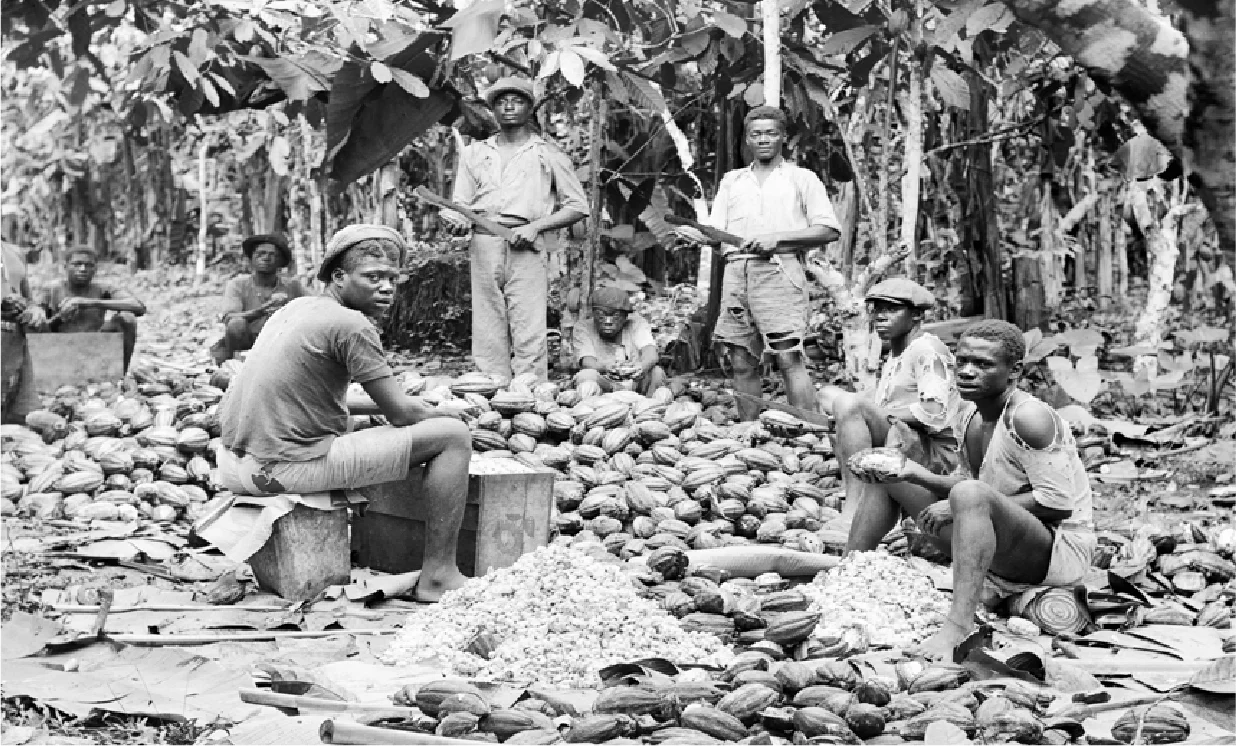

From Tamil labourers harvesting cocoa pods under colonial rule to today’s migrant workers on palm oil plantations — the faces change, but the structures of exploitation remain.

Credit left image: Tamil labourers – Crown Copyright Reserved.

Issued by the Central Office of Information, London.

Credit right image: Migrant labourer in palm oil –

photo by Mohd Suhaimi Mohamed Yusuf/The Edge)

Issued by the Central Office of Information, London.

Credit right image: Migrant labourer in palm oil –

photo by Mohd Suhaimi Mohamed Yusuf/The Edge)

62%

of Indians feel discriminated,

only 28% feel fairly treated

62%

of Malaysian Indian children move upwards in their class position, compared to Malaysian Chinese Children (around 89%) and Bumiputera children (around 73%)

227,600

Indian B40 households earn RM2,672/month

40%

of the 2.6 million Indians

are stuck at the bottom of

the income distribution

Background Photo by Mogan Selvakannu

From Tamil labourers harvesting cocoa pods under colonial rule to today’s migrant workers on palm oil plantations — the faces change, but the structures of exploitation remain.

Credit left image: Tamil labourers – Crown Copyright Reserved.

Issued by the Central Office of Information, London.

Credit right image: Migrant labourer in palm oil –

photo by Mohd Suhaimi Mohamed Yusuf/The Edge)

Issued by the Central Office of Information, London.

Credit right image: Migrant labourer in palm oil –

photo by Mohd Suhaimi Mohamed Yusuf/The Edge)

62%

of Indians feel discriminated,

only 28% feel fairly treated

62%

of Malaysian Indian children move upwards in their class position, compared to Malaysian Chinese Children (around 89%) and Bumiputera children (around 73%)

227,600

Indian B40 households earn RM2,672/month

40%

of the 2.6 million Indians

are stuck at the bottom of

the income distribution